I have a friend that I know from my time in Minnesota. She identifies as a white person, which is not all that uncommon in a state that Chris Rock famously described as having a Black population of two (Prince and Kirby Puckett). If you saw her walking down the street, you would never suspect anything different: very light skin and an accent straight out of a scene from Fargo or Feeling Minnesota. Partnered with a Black man, you would not be able to tell the two of them apart from any other interracial couple (and there are many) in the Twin Cities.

But my friend ain’t exactly descended from Vikings. You see, she is at least a quarter Native American. In Minnesota, a state with a large and politically active Native community, that can be quite beneficial when you are going through either of the state’s university systems. This is because of the legacy of oppression towards Native people in the state. For example, my alma mater, the University of Minnesota Morris, was formed in 1960 by adding a liberal arts component to the University of Minnesota’s West Central School for Agriculture (WCSA). The WCSA was founded on the site of the old Sisters of Mercy-run Morris Industrial School for Indians, which had closed in 1909, the year before the WCSA was formed. Due to this history, any person that can prove their Native background to a certain degree receives free tuition.

Although my friend did not attend UMM with me, it is not hard to find such programs at many of the state’s universities. I used to ask her why she did not avail herself of those opportunities; after all, there were a ton of “Native Americans” at Morris that you would be hard-pressed to find at a pow-wow (a common event at the University) or at a Circle of Nations Indian Association student group meeting. She would simply say, “I was raised as a white woman. I was not raised as a Native American, and it would be wrong for me to claim a community that is not mine simply to get financial benefit.”

Makes sense, right? But judging by the reaction to Rachel Dolezal, the former NAACP chapter chair in Spokane, Washington who was born to white parents but identifies as Black, and now University of California Riverside professor Dr. Andrea Smith, sensibility no longer appears to be on the menu.

—

Dolezal’s road to perdition, as most people living in non-rock-based domiciles will be able to tell you, began when her parents dropped the dime on her born ethnicity. From there, all hell broke loose. It was the major story in every news outlet imaginable. By the time the story began to wind down, Dolezal was enough of a known quantity to warrant my receipt of not one, not two, but three breaking news alerts from different media outlets to my phone informing me of her resignation from the chapter presidency of a NAACP branch in a city with a Black population of barely two percent. The Andrea Smith story does not threaten to explode in the same way that Dolezal’s did. This might be due to the fact that, in the wake of nine dead at an African Methodist Episcopal church in South Carolina and at least seven church burnings in the last couple of weeks, people have decided that other things may warrant their full attention.

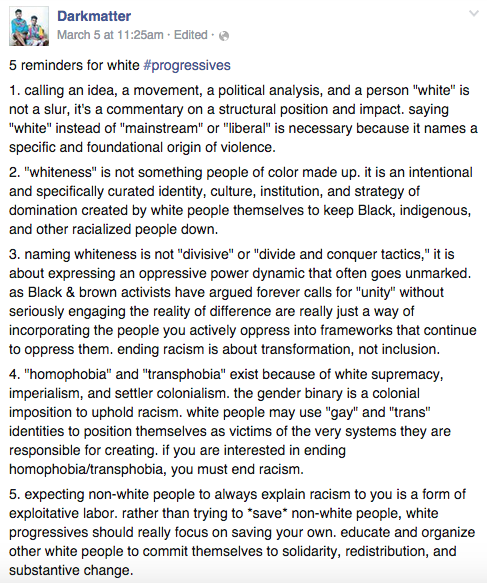

But we should not be under any illusions that absent such inhuman barbarity unseen in the United States since the days of Klan night rides through the South, the Smith story would not have been one that blew up in much the same way. I have blogged a lot about identity politics and the ways in which individual instances have manifested in some incredibly nasty and solidarity-killing ways. But it is time to go beyond the sturm und drang of social media slap fights to examine just how we got to this point. How have we arrived at the point where putatively liberal and progressive activists, organizations, and websites are enthusiastically repeating the foundations of an ideology once confined to far-right reactionaries?