In 2012 a federal lawsuit was filed against the restaurant chain IHOP and franchisee, Anthraper Investments Inc. on behalf of four Arab, Muslim managers in Texas, all of whom were fired in 2010. This lawsuit alleged in part that their terminations were unlawful and discriminatory in nature, and came after the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) found that their accusations had merit—not only had these men faced discriminatory harassment at work based on their race, and religion, there were witnesses, and corroborating evidence, determining that there was “reasonable cause to believe that…Arabs were discriminatorily harassed and discharged based on national origin.”

One of the most revealing incidents came during an employee meeting, during which Larry Hawker, hired to replace one of the fired managers, told IHOP workers that, “Arab men treat women poorly and with disrespect. We’re going to let these people go and have new faces coming in.” Prior to this event, and before their respective terminations, the district manager would be emailed warnings in time for the anniversary of the September 11th attacks, asking that Arab and Muslim employees “lay low”.

The CEO of this specific IHOP chain, John Anthraper, even referred to Muslims waiting to break their fasts during Ramadan as “dogs”, and would complain that any work related incidents that occurred at one of his stores came about as a result of the district manager hiring “those fucking Arab friends” of his. And so, these four men sought damages for employment discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 1981 of the Civil Rights Act of 1991, and the Texas Labor Code.

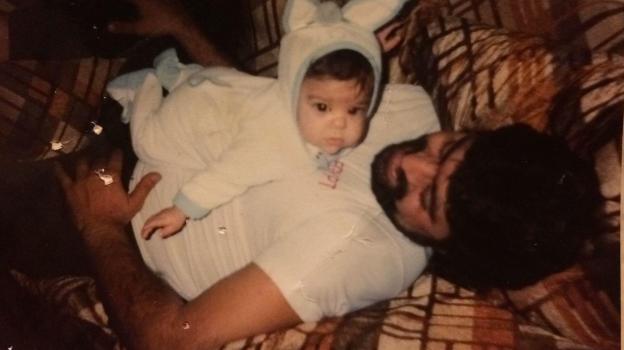

One of these men—the man whose face would be plastered across countless publications and television screens as the story and subsequent backlash went viral—was my father.